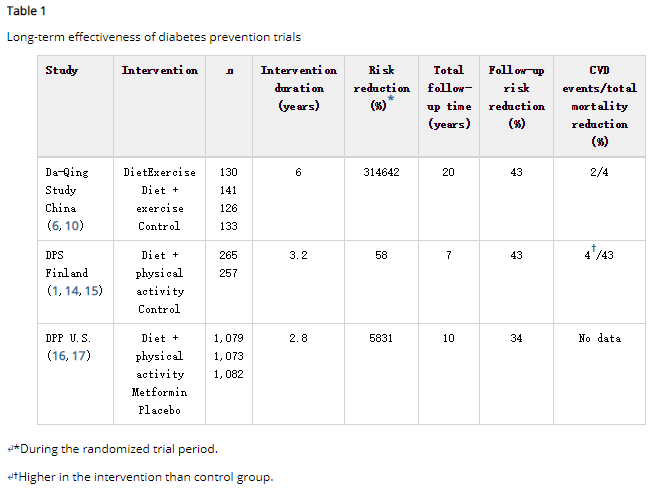

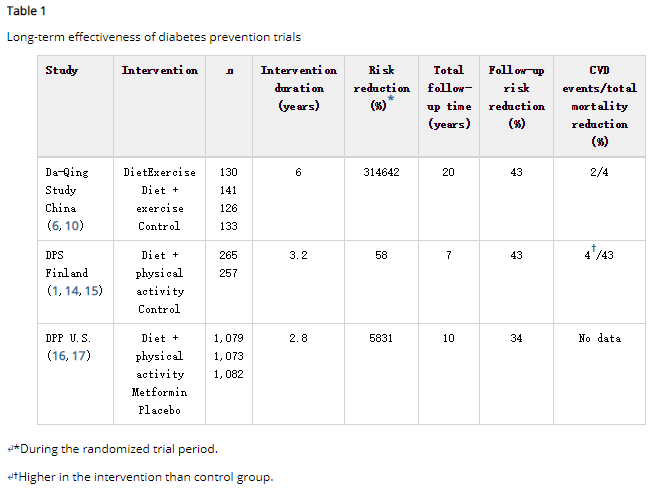

通过生活方式干预来预防2型糖尿病高危人群的潜在作用已经在几个临床试验中得到证实。这些研究主要着重于增加体育活动、改变饮食习惯以及减轻超重参与者的体重。同时纠正几个危险因素的综合方法似乎是问题的关键。此外,对持续时间有限的生活方式干预的长期随访研究似乎对风险因素和糖尿病发病率有长期的后续效应(表1)。

这项研究的证据鼓舞了世界各地的国家和地方当局以及卫生保健提供者启动预防2型糖尿病及其并发症的计划和活动。基于临床试验和“现实世界”实施方案的经验,IMAGE(制定和实施欧洲糖尿病预防指南和培训标准)研究组系统地整理了信息。IMAGE的可交付成果包括:欧洲预防2型糖尿病循证指南、欧洲预防2型糖尿病工具包、欧洲预防2型糖尿病质量指标。现在需要的是政治支持,以制定预防糖尿病的国家行动计划。成功的预防活动的先决条件包括:有政府和非政府层面以及不同层次的医疗保健领域若干利益攸关方的参与。此外,还必须建立结构来确定高危人员并管理干预、随访和评估。

观察性研究为多种生活方式相关因素增加或降低2型糖尿病风险提供了有力证据。因此,在预防2型糖尿病时,不仅要注意肥胖等单一因素,还要同时注意几个因素。芬兰糖尿病预防研究(DPS)明确地证明了这一方法。在最初的试验期间,如果糖耐量受损(IGT)的高危人群达到了5个预先设定的生活方式目标中的4个或5个,那么他们中没有一个人发展成糖尿病(1)。这些目标如下:

这样的目标相对来说比较适度,因此许多人都有可能达到。此外,实行这样的生活方式是长期,甚至终身可行的。然而,有人批评这些试验数据过于乐观,因为试验人群包括自愿参与这种生活方式干预试验的个人。有人质疑这种试验结果是否或在何种程度上可以适用于一般民众。尽管这种批评可能是正确的,但参与试验的人都是典型的糖耐量受损患者,他们超重、相对久坐不动、饮食在很多方面都与建议不一致(2)。

对生活方式干预试验进行长期后续观察期间所观察到的长期效应——一个具有前景的发现是,持续有限时间段的生活方式干预似乎对2型糖尿病的发病率具有长期的残余效应。第一项表明风险可能持续降低的研究是马尔默可行性研究。最初,运动和饮食(n = 161)对IGT男性的2型糖尿病发病率的效应,与参考组(n = 56)的进行了比较,参考组由不想进行生活方式干预的类似男性构成。因此,这些组没有随机分配。到5年研究期结束时,11%的干预组和29%的参照组患有糖尿病。12年的随访结果显示,前IGT干预组男性的全因死亡率低于仅接受“常规治疗”的非随机糖耐量受损组男性(6.5 vs. 14.0%) 1,000人年,P = 0.009)。前IGT干预组的死亡率实际上与葡萄糖耐量正常的男性相似。

1986年在中国大庆开展了一项大规模的人群筛查计划(110,660人接受口服葡萄糖耐量试验筛查)以确定糖耐量受损患者。研究对象的随机化不是随机进行的,但是33个参与诊所(整群随机化)随机分组,根据四种特定干预方案中的一种进行干预(仅饮食,单独运动,饮食运动结合或无)。总共有577名患有糖耐量受损的男性和女性参加了这项试验,其中533名参加了1992年6年生活方式干预结束时的测量。大庆研究参与者相对精简;基线时的平均BMI为25.8 kg / m2。在指定饮食干预的诊所中,如果BMI为.25 kg / m2,则鼓励参与者减轻体重,目标为24 kg / m2;否则,建议使用高碳水化合物(55-65%)和中等脂肪(25-30%)的饮食。风险因素模式的总体变化相对较小。瘦体重患者的体重没有变化,基线BMI为0.25 kg/m2的受试者体重减少1 kg。同样,这表明单独体重可能不是预防2型糖尿病最关键的问题;此外,其他生活方式问题很重要,而体重可作为几种饮食和活动因素的总结指标。

与对照组(68%)相比,三种(单纯饮食、单纯运动、饮食-运动相结合)干预组(41-46%)的2型糖尿病累积6年发病率较低。大青研究队列的20年随访分析于2008年发表。结果显示,联合干预组与没有干预的对照组相比,2型糖尿病发病率持续下降;此外,在干预后期间,风险降低基本保持不变。然而,随访期间2型糖尿病的发病率普遍较高:在最终分析中,80%的干预参与者和93%的对照参与者患有2型糖尿病。

此外,这项为期20年的随访研究旨在评估生活方式干预是否会对心血管疾病(CVD)或死亡率的风险产生长期影响。结果显示,对照组或三个干预组合的CVD事件,CVD死亡率或总死亡率无统计学差异。观察到CVD死亡率显着降低17%,这可以看出至少暗示生活方式干预的益处。

芬兰的DPS是一项多中心试验,从1993年到2001年在芬兰的五个诊所进行。该研究的主要目的是确定患有糖耐量受损的高危个体,是否可以只通过改变生活方式来预防2型糖尿病。该研究共招募了522名男性和女性。参与者被随机分配到对照组或强化干预组。

干预组的基线体重平均减少4.5 kg,对照组受试者为1.0 kg(P <0.001),第一年和3年后体重减轻分别为3.5和0.9 kg(P,0.001)。此外,干预组的中心性肥胖和葡萄糖耐量指标在1年和3年随访检查中均显着高于对照组。在1年和3年的考试中,干预组受试者根据饮食和运动日记报告他们的饮食和运动习惯有显着更有益的变化。与对照组相比,干预组代谢综合征的成分也显着改善。

截至2000年3月,当研究的随访中位时间为3年时,在522例随机分入DPS的糖耐量受损患者中共诊断出86例糖尿病病例。干预组糖尿病累积发生率为11%(95%CI 6-15),4年后对照组为23%(95%CI 17-29); 因此,与对照组相比,干预组试验期间患糖尿病的风险降低了58%(P <0.001)。事后分析表明,除了减轻体重外,采用中等脂肪和高纤维含量的饮食,以及增加体力活动,与糖尿病风险降低独立相关。

使用在DPS延长随访期间收集的数据进行的分析显示,在中位总共7年的总体随访后,2型糖尿病的累积发病率显着下降。总跟进期间的相对风险降低为43%。干预期间无糖尿病患者干预对糖尿病风险的影响:在干预后进行的3年中位随访后,在有221名风险人群的干预组中有31个新增2型糖尿病案例,而在有185名风险人群的对照组中有38例。相应的发病率分别为4.6和7.2/100人年(对数秩检验,P = 0.0401)(即相对风险降低36%)。

DPS的10年随访结果显示干预组和对照组的总死亡率(2.2对3.8 / 1,000人年)和心血管疾病发病率(22.9对22.0 / 1000人年)没有差异。有趣的是,当DPS组(基线时的所有IGT)与芬兰人群为基础的IGT患者队列进行比较时,DPS队列的校正风险比率较低:干预组和对照组的总死亡率分别为0.21(95%CI 0.09-0.52)和0.39(0.20)-0.79),心血管事件发生率为0.89(0.62±1.27)和0.87(0.60-1.27)。

糖尿病预防计划(DPP)是一项在美国进行的多中心随机临床试验。它比较了三种干预措施的有效性和安全性:强化生活方式干预或标准生活方式建议与二甲双胍或安慰剂相结合。饮食干预的目标是通过消耗健康的低热量低脂饮食来实现并保持7%的体重减轻,并且每周150分钟进行中等强度的体力活动(例如快走)。与安慰剂对照组相比,2.8年后的强化生活方式干预减少了2型糖尿病风险平均随访58%。生活方式干预也优于二甲双胍治疗,与安慰剂相比,其导致2型糖尿病风险降低31%。在1年的访问中,平均体重减轻为7kg(~7%)。

在发现同样在DPP中,2型糖尿病发病率降低58%与生活方式干预相关,与DPS类似,随机试验停止,参与者被邀请参加糖尿病预防计划成果研究)。在随访期间,所有参与者,无论其原始治疗组如何,都获得了生活方式咨询。在10年的总体随访期间(从最初的随机化开始),与对照组相比,原始生活方式干预组的2型糖尿病发病率降低了34%。然而,在干预后随访期间,所有治疗组的2型糖尿病发病率相似(前干预组为每100人年5.9人,安慰剂对照组为5.6%),证实了在前安慰剂对照组开展的生活方式干预取得了成功,即使在没有任何积极干预的几年随访以后。

[附]英文原文

Long-Term Benefits From Lifestyle Interventions for Type 2 Diabetes Prevention

The potential to prevent type 2 diabetes in high-risk individuals by lifestyle intervention was established in several clinical trials. These studies had a strong focus on increased physical activity and dietary modification as well as weight reduction among overweight participants. The key issue seems to be a comprehensive approach to correct several risk factors simultaneously. Furthermore, long-term follow-up studies of lifestyle interventions lasting for a limited time period seem to have a long-lasting carry-over effect on risk factors and diabetes incidence (Table1).

The research evidence has inspired national and local authorities and health care providers all over the world to start programs and activities to prevent type 2 diabetes and its complications. Based on the experiences from the clinical trials, as well as from the “real world” implementation programs, the IMAGE (Development and Implementation of a European Guideline and Training Standards for Diabetes Prevention) Study Group collated information in a systematic manner. The IMAGE deliverables include a European evidence-based guideline for the prevention of type 2 diabetes, a toolkit for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in Europe, and the quality indicators for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in Europe. What is needed now is political support to develop national action plans for diabetes prevention. The prerequisites for successful prevention activities include involvement of a number of stakeholders on the governmental and nongovernmental level as well as on different levels of health care. Furthermore, structures to identify high-risk individuals and manage intervention, follow-up, and evaluation have to be established.

Observational studies have provided firm evidence that multiple lifestyle-related factors either increase or decrease the risk of type 2 diabetes. Thus, in type 2 diabetes prevention, it is important to pay attention not only to one single factor such as obesity but also to several factors simultaneously. This method was unequivocally demonstrated by the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS), where none of the high-risk individuals with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) developed diabetes during the initial trial period if they reached four or five out of five predefined lifestyle targets (1). These targets were as follows: weight loss .5%, intake of fat,30% energy, intake of saturated fats ,10% energy, increase of dietary fiber to $15 g/1,000 kcal, and increase of physical activity to at least 4 h/week. Such targets are relatively modest and therefore possible to reach by many people. Moreover, to practice such a lifestyle is feasible for the long term, even for an entire lifetime.However, the trial data have been criticized for presenting an over-optimistic outlook, since the trial population comprised individuals who volunteered to participate in such a lifestyle intervention trial. It has been questioned whether or to what extent such trial results can be translated to the general population. Although this critique may be valid, the individuals participating in the trial were typical Finnish people with IGT who were overweight, were relatively sedentary, and whose diet was discordant with recommendations in many ways (2).

LONG-TERM EFFECTS OBSERVED DURING THE EXTENDED FOLLOW-UP OF LIFESTYLE INTERVENTION TRIALS—A promising finding is that lifestyle interventions lasting for a limited time period seem to have a long-lasting carry-over effect on type 2 diabetes incidence. The first study to suggest that a sustained risk reduction may exist was the Malmö Feasibility Study (8). Originally, the effect of exercise and diet (n = 161) on incidence of type 2 diabetes among men with IGT was compared with a reference group (n = 56) of similar men who did not want to join the lifestyle intervention. Thus, the groups were not assigned at random. By the end of the 5-year study period, 11% of the intervention group and 29% of the reference group had developed diabetes. The 12-year follow-up results (9) revealed that all-cause mortality among men in the former IGT intervention group was lower than that among the men in the nonrandomized IGT group who received “routine care” only (6.5 vs. 14.0 per 1,000 person-years, P = 0.009). Mortality in the former IGT intervention group was actually similar to that in men with normal glucose tolerance.

A large population-based screening program (110,660 individuals screened with an oral glucose tolerance test) to identify people with IGT was carried out in Da Qing, China, in 1986 (6). The randomization of study subjects was not done at random, but the 33 participating clinics (cluster randomization) were randomized to carry out the intervention according to one of the four specified intervention protocols (diet alone, exercise alone, diet-exercise combined, or none). Altogether, 577 men and women with IGT participated in the trial, and of them, 533 participated in the measurements at the end of the 6-year lifestyle intervention in 1992. The Da Qing study participants were relatively lean; the mean BMI was 25.8 kg/m2 at baseline. In clinics assigned to dietary intervention, the participants were encouraged to reduce weight if BMI was .25 kg/m2, aiming for, 24 kg/m2; otherwise, a high-carbohydrate (55-65%) and moderate-fat (25-30%) diet was recommended. The overall changes in risk factor patterns were relatively small. Body weight did not change in lean subjects, and there was a modest,1 kg reduction in subjects with baseline BMI .25 kg/m2. Again, this indicates that body weight alone may not be the most critical issue in the prevention of type 2 diabetes; also, other lifestyle issues are important, whereas body weight may work as a summary indicator of several dietary and activity factors.

The cumulative 6-year incidence of type 2 diabetes was lower in the three (diet alone, exercise alone, diet-exercise combined) intervention groups (41-46%) compared with the control group (68%). The 20-year follow-up analyses of the original Da Qing study cohort were published in 2008 (10). The results showed that the reduction in type 2 diabetes incidence persisted in the combined intervention group compared with control participants with no intervention; furthermore, the risk reduction remained essentially the same during the postintervention period. However, type 2 diabetes incidence during the follow-up was generally high: in the final analyses, 80% of the intervention participants and 93% of the control participants had developed type 2 diabetes.

Furthermore, the 20-year follow-up study aimed to assess whether the lifestyle intervention had a long-term effect on the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or mortality. The results showed no statistically significant differences in CVD events, CVD mortality, or total mortality either in the control group or the three intervention groups combined. A non-significant 17% reduction in CVD death was observed, which can be seen at least suggestive for benefits of lifestyle intervention.

The Finnish DPS was a multicenter trial carried out in five clinics in Finland from 1993 to 2001. The main aim of the study was to find out whether type 2 diabetes is preventable with lifestyle modification alone among high-risk individuals with IGT. A total of 522 men and women were recruited into the study. The participants were randomly allocated either into the control group or the intensive intervention group (2).

Body weight reduction from baseline was on average 4.5 kg in the intervention group and 1.0 kg in the control group subjects (P , 0.001) after the first year and at 3 years, weight reductions were 3.5 and 0.9 kg (P , 0.001), respectively. Also, indicators of central adiposity and glucose tolerance improved significantly more in the intervention group than in the control group at both the 1-year and 3-year follow-up examinations. At the 1-year and 3-year examinations, intervention group subjects reported significantly more beneficial changes in their dietary and exercise habits, based on dietary and exercise diaries (2). The components of the metabolic syndrome also improved significantly in the intervention group compared with the control group (11).

By March 2000, a total of 86 incident Cases of diabetes had been diagnosed among the 522 subjects with IGT randomized into the DPS when the median follow-up duration of the study was 3 years. The cumulative incidence of diabetes was 11% (95% CI 6–15) in the intervention group and 23%(95%CI 17–29) in the control group after 4 years; thus, the risk of diabetes was reduced by 58% (P , 0.001) during the trial in the intervention group compared with the control group (1). Post hoc analyses have shown that in addition to weight reduction, adopting a diet with moderate fat and high fiber content (12), as well as increasing physical activity (13), was independently associated with diabetes risk reduction.

An analysis using the data collected during the extended follow-up of the DPS revealed that after a median of 7 years total follow-up, amarked reduction in the cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes was sustained (14). The relative risk reduction during the total follow-up was 43%. The effect of intervention on diabetes risk was maintained among patients who after the intervention period were without diabetes: after the median postintervention follow-up time of 3 years, the number of incident new cases of type 2 diabetes was 31 in the intervention group among 221 people at risk and 38 in the control group among 185 people at risk. The corresponding incidences were 4.6 and 7.2 per 100 person-years, respectively (log-rank test, P = 0.0401) (i.e., 36% relative risk reduction).

The 10-year follow-up results of the DPS showed that total mortality (2.2 vs. 3.8 per 1,000 person-years) and cardiovascular morbidity (22.9 vs. 22.0 per 1,000 person-years) were not different between the intervention and control groups (15). Interestingly, when the DPS groups (all IGT at baseline) were compared with a Finnish population-based cohort of people with IGT, the adjusted hazard ratios were lower in the DPS cohort: 0.21 (95% CI 0.09–0.52) and 0.39 (0.20-0.79) for total mortality in the intervention and control groups, respectively, and 0.89 (0.62 1.27) and 0.87 (0.60–1.27) for cardiovascular events.

The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) was a multicenter randomized clinical trial carried out in the U.S. (16). It compared the efficacy and safety of three interventions: an intensive lifestyle intervention or standard lifestyle recommendations combined with metformin or placebo. The goals of the dietary intervention were to achieve and maintain 7% weight reduction by consuming a healthy low-calorie low-fat diet and to engage in physical activities of moderate intensity (such as brisk walking) $150 min per week. The intensive lifestyle intervention re- duced type 2 diabetes risk after 2.8 years mean follow-up by 58% compared with the placebo control group. Lifestyle intervention was also superior to metformin treatment, which resulted in a 31% type 2 diabetes risk reduction compared with placebo. At the 1-year visit, the mean weight loss was 7 kg (~7%).

After finding that also in the DPP a 58% risk reduction in type 2 diabetes incidence was associated with lifestyle intervention, similar to that in the DPS, the randomized trial was stopped and the participants were invited to join the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study (17). During the follow-up, all participants, regardless of their original treatment group, were offered lifestyle counseling. During the overall follow-up of 10 years (from the initial randomization), type 2 diabetes incidence in the original lifestyle intervention group was reduced by 34% compared with the control group. However, during the postintervention follow-up, type 2 diabetes incidence was similar in all treatment groups (5.9 per 100 person- years in the former intervention group and 5.6% in the placebo control group), confirming that lifestyle intervention that was initiated in the former placebo control group was successful, even after several years of follow-up without any active intervention.

【附】原文链接:

http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/34/Supplement_2/S210